“The most famous and controversial of all obedience experiments.”

Richard Gross

When I was studying A-Level Psychology (many years ago), Milgram’s obedience study was one of the first we had to research. It left me hooked on psychology and when I started university, we were able to go much deeper into the study and its real-life implications. This study on obedience, as well as Phillip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment on conformity, have left me seeing the human race in a very different way. I no longer see good and bad people as clear as black and white. In the right situation/environment, anyone is capable of anything. Anything…

PSA: This will be an extremely long post as this study, it’s findings and the impact it has had on psychology and society ever since is extraordinary and I would only feel guilty if I underplayed Milgram’s study.

(Also, here is a previous post I made on Zimbardo’s wild study on conformity)

You buckled in? Ok, so here we go!!

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram dramatically changed our understanding of human obedience when he published Behavioural Study of Obedience way back in 1963. In this paper, he detailed results from an experiment that appeared to suggest that a majority of people are capable of causing extreme harm to others when they are told to do so by a figure of authority. It is caused people to question the limits of psychological experiments (NB: In Milgram and Zimbardo’s time, ethics were flip-floppy, however now they are very strict in what you can/cannot do with someone, thankfully!).

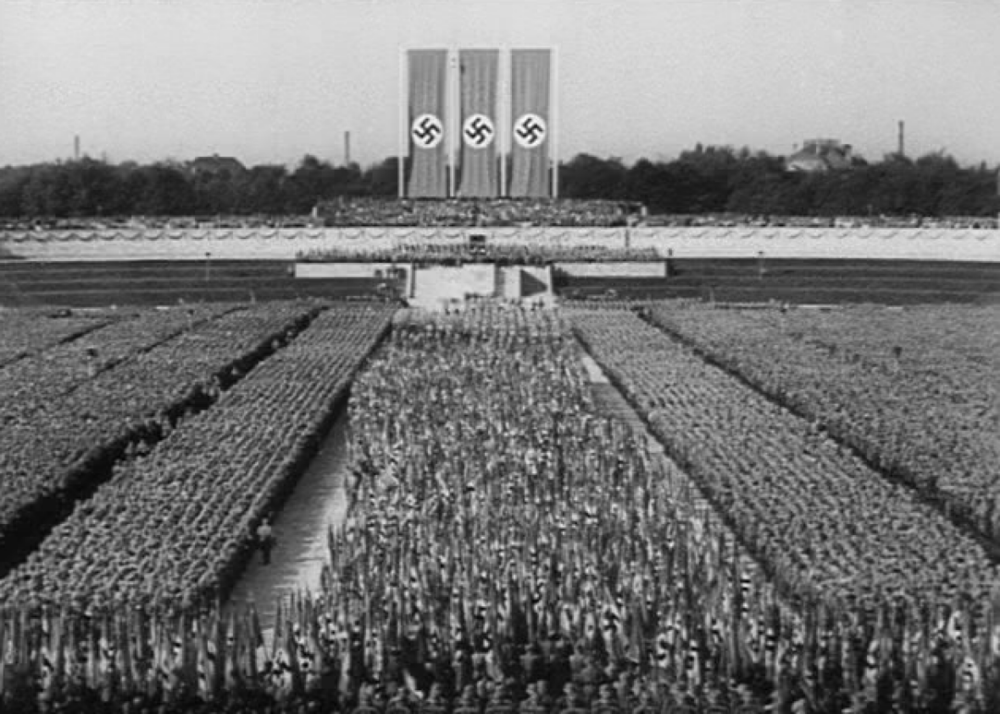

Milgram has originally became interested in studying obedience during the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. The prevailing view was that there was something inherently different about these 20th century Germans… In the 1950s, psychologists such as Theodor Adorno had suggested that the Germans appeared to have certain personality characteristics which left them especially susceptible to committing the atrocities during the Holocaust. During his trial, Adolf Eichmann claimed that he was simply “following orders”, and this claim led Milgram to set out to investigate if this could be true. Would an ordinary person, like you or me, lay aside what we know to be right or wrong merely because we are ordered to do so? Milgram’s study went on to demonstrate the important aspects of the relationship between authority and obedience, and it remains one of the most controversial experiments in the history of psychology.

The Power of the Group

Milgram believed that it was the situation of World War II and the compulsion to obey – rather than the disposition of the Germans – that had enabled the cruelty conducted at the hands of the Nazis. He maintained that the behaviour was a direct result of the situation, and any of us might have behaved identically in the same context. In the late 1950s, Milgram had worked extensively with Solomon Asch on his conformity studies (he shall also be getting a post soon also!) and had witnessed people agreeing with the decisions of a group, even when they knew these decisions to be wrong. These experiments showed that people are prepared to do or say things that conflict with their own sense of reality. Would they also allow their moral judgements to be affected by the authority of a group or even single figure?

The Milgram Experiment

Milgram set out to test if normally kind, likeable people could be made to act against their own moral values in a setting where some kind of authority held sway. He devised an investigation of how obedient a random selection of “ordinary” men would be when they were told by an authority figure to administer electric shocks to another person. The experiment took place in lab in Yale University in 1961 as Milgram was currently a professor of psychology in the department. The participants were recruited through a newspaper advert with a total of 40 men selected from a wide range of occupations, including teachers, postal workers, engineers, labourers and salesmen. They were each paid $4.50 for their participation (good enough bucks in those days!); they were given the money as soon as they arrived at the laboratory, and they were told that the money was theirs to keep regardless of what happened during the experiment.

In the laboratory, Milgram had built a fake but very realistic looking electric shock generator. It had 30 different switches which were marked with 15-volt increments, with labels that indicted the intensity of different ranges of shock levels. These ranged from “slight shock” at one end, to “extreme intensity shock”, “danger: severe shock”, and finally the last one on the far end simply marked “XXX”.

The role of the experimenter, or “scientist” was played by a biology teacher who introduced himself to participants as Jack Williams. In order to give the air of authority, he was given a grey laboratory technicians coat and maintained a stern and emotionless demeanour throughout each of the experiments.

The participants were told that the study intended to investigate the effects of punishment on learning. They were told that of two volunteers, one would have the role of learner and the other would play the role of the teacher. In reality, one of the volunteers was actually a stooge, Mr Wallace, a very likable accountant who had been trained by researchers to play the role of the victim. When Mr Wallace and the genuine participant drew paper from a hat to determine which role they would play, the draw was always rigged so that Mr Wallace took on the role of the “learner” in every instance. In full view, the “learner” was strapped into an “electric chair” with an electrode attached to his wrist. The participant was told that this electrode was attached to the shock generator located in an adjacent room. The participant heard the “scientist” tell the “learner” (Mr Wallace) that “although the shocks can be extremely painful, they cause no permanent damage”. To make the situation appear more authentic, the scientist then wired up the participant and gave him a sample shock of 45 volts – which was in fact the only shock strength that the generator could produce.

At this point, the participant was moved to the room containing the shock generator and asked to assure the role of “teacher”. He was asked to read a series of word pairs (such as “blue-girl”, “nice-day”) aloud for the learner to memorise. After this, he was to read out a series of single words; the learner’s task was to recall the pairing work in each case and to indicate his answer by pressing a switch that illuminated a light on the shock generator. If the learner’s answer was correct, the questions continued; if the answer was incorrect, the participant was instructed to tell the learner that the correct answer and then proceeded to announce the level of shock they were about to administer. Participants were instructed to increase the shock level by 15 volts (in other words, keep moving up the shock scale on the machine) with every wrong answer.

Applying the Shocks

As part of the experiment, the learner had been briefed to answer incorrectly to around one question in every four, to ensure that the participant would be required to start applying shocks. During the experiment, the learner would pound the wall once when the voltage had reached 300V, and shout: “I absolutely refuse to answer any more! Get me out of here! You can’t hold me here! Get me out!”

As the shock level increased, the learner would then shout more frantically and then eventually cease making any noise at all, with questions being met with nothing more than an eerie silence… The participant was told to treat this silence as an incorrect answer and to continue to apply the increasing levels of shocks. If the participant expressed any misgivings or unwillingness, the scientist would give them a verbal prod to encourage them. These verbal prods ranged from a simple request to continue with the study, to finally being told that they had no choice but to go on. If the participant continues to refuse to obey after the last prod, the experiment was terminated.

“With numbing regularity, good people were seen to knuckle under the demands of authority and preform actions that were callous and severe.”

Stanley Milgram

In advance of the experiment, Milgram had asked several different groups of people, including ordinary members of the public as well as psychologists and psychiatrists, how far they would go when asked to administer the electric shocks. Most people believed that people would stop at a level that caused pain, and the psychiatrists predicted that at most 1 in 1,000 would continue to the highest level of shock. Astonishingly, when the experiment took place, all 40 of the participants obeyed the commands to administer the electric shocks up to 300 volts. Only five people refused to continue after that point; 65% of the participants obeyed the instructions of the scientist right to the end, obeying commands to administer shocks to the top level of 450 volts.

Their discomfort at doing so was often evident; many showed signs of severe distress, tension and nervousness over the course of the experiment. They stuttered, trembled, sweated, groaned, broke into a fit of nervous laughter, and three people had full blown seizures. In every instance, the participant stopped and questioned it at some point; some even offered to refund the money they were paid at the beginning. Interviews after the experiments confirmed that, with only a few exceptions, participants had been completely convinced that the “learning experiment” was real.

All participants were fully debriefed, so they understood what had actually taken place, and they were asked a series of questions to test that they were not emotionally harmed by the experience. The participants were also reunited with the “learner” so that they could be reassured that no actual shocks were administered and that he came to no harm.

Feeling Obliged to Obey

Milgram noted several features of the experiment that may have contributed to such high levels of obedience; for example, the fact that it took place in the prestigious Yale University gave it credibility. In addition, participants believed that the study was designed to advance knowledge, and they had been assured that the shocks was designed to advance knowledge, and they had been assured that the shocks were painful and not dangerous. Being paid may have increased their sense of obligation, as did the fact that they had volunteered to take part. Milgram ran many variations on the study but changing the context had only minor effects on the results.

Milgram wanted to see if the inclination to obey authority figures can become the major factor in determining behaviour, even in extreme circumstances. It is clear from the reactions and responses of the participants that obeying the scientist was violating their own sense of morality and negatively affecting them both physically and emotionally, but the pressure to comply was simply too powerful to defy in most cases.

This sense of obedience, Milgram felt, comes from the fact that people are socialised from a very young age (by parents and teachers) to be obedient and to follow orders – especially the rules set by the authority figures in the world. As Milgram says, “obedience is as basic an element in the structure of social life as one can point to… it serves numerous productive functions”. But equally, the inhumane policies of the death camps in World War II “could only have been carried out on a massive scale if very large numbers of persons obeyed orders”. His experiments clearly demonstrated that normally harmless folk can become capable of committing such cruel acts when a situation pressures them to do so.

In describing his results, Milgram also turned to the theory of conformism, which states that when a person has neither the ability nor expertise to make a decision, he will look to the group to decide how to behave. Conformity can limit and distort a person’s response to a situation and seems to result in a diffusion of responsibility – something which Milgram felt was crucial to comprehending the atrocities carried out by the Nazis. However, the conflict between a person’s conscience and external authority exerts a huge internal pressure, and Milgram felt think accounted for the extreme distress experienced by the participants in his study.

Ethical Concerns

There were many ethical concerns associated with Milgram’s study, I wonder why?! When it was first published, the ensuing controversy was so great, that the American Psychological Association (APA) revoked his membership for a full year. However, it was eventually reinstated and Milgram’s 1974 book Obedience to Authority received the annual Social Psychology Award.

The major concern was that the participants in the experiment were explicitly deceived, both about the nature of the study and about the reality of electric shocks. Milgram’s defence was that he could not have obtained realistic results without employing deception, and all of the participants were debriefed afterwards. Self-knowledge, he argued is a valuable asset, despite the discomfort that the participants may have felt when they were forced to confront the fact that they behaved in a previously unthinkable way.

However, many psychologists remained uneasy and this study was ultimately crucial in the development of ethical standards of psychological experimentation. It helped to define important principles such as the avoidance of intentional deceit of participants, and the need to protect experimental participants from emotional suffering.

Virtual Torture

In 2006, the psychologist Mel Slater set out to see what the effect would be if participants were made explicitly aware that the situation was not real. His replication used a computer simulation of the learner and shock process, so the participants which were administering the shocks were completely aware that the learner was computer generated. The experiment was run twice; firstly, with the virtual learner communicating only by text, and then with the computer-generated model visible on screen. Those with only text contact with the learner had little trouble in administering the shocks, but when the virtual learner was visible, participants acted exactly as they had in Milgram’s original experiment.

Society Demands Obedience

The very notion of a society rests on an understanding that individuals are prepared to relinquish some personal autonomy and look to others of higher authority and social status to make decisions on a larger scale or from a higher, broader perspective. Even the most democratic of societies requires the rulings of a recognised, legitimate authority to take precedence over individual self-regulation, in pursuit of the greater collective good. In order for any society to function, its population must agree to obey the rules. Legitimacy is, of course, the key and there are countless historical examples of people using their authotiy to persuade others to commit crimes against humanity. For example, the behaviour of the Nazis during World War II had been attributed to a prevalence of the “authoritarian personality” in the population. In addition, the American soldiers in Vietnam reported that their behaviour became unacceptable by degrees – as with the shock generator – until they found themselves murdering innocents.

“In wartime, a soldier does not ask whether it is good or bad to bomb a hamlet.”

Stanley Milgram

Equally important, Milgram showed that it is “not so much the kind of person a man is, as is the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act”. Instead of examining personalities to explain crimes, he says, we should examine the context or situation.

Milgram’s study was heavily criticised at the time, not least because it painted an unappealing and chilling portrait of human nature. After all, it is easier to believe that the acts of the Nazis compared to the general population were due to fundamental differences rather than accept that in certain situations, many of us are capable of committing extraordinary acts of violence. Milgram held up a light to the dark realities concerning power and the consequences of our tendency to obey authority figures, and in so doing, he simultaneously absolved and made villains of us all.

And et voila, that’s the tea on Milgram! If you would like to find out more about this world changing study, here are some more links for to explore! There is also a 2015 movie based on Milgram and his experiment!